Recent History

The "Gaffe" in the American Presidential Debates

The focus on the “gaffe” as a defining feature of presidential debate coverage, and of presidential campaign coverage in general illustrates several phenomena in American politics and political news coverage: the focus on aspects of the debate that often reflect character judgements more than issues, the need for “bite-sized” pieces of news out of the debates in the context of the 24/7 news cycle, and the power of the media to influence perceptions of the candidates through pundit coverage. These effects combine to create a shallow debate format in which the goal of both candidates is to studiously avoid any unscripted statements and re-iterate their campaign’s message, to avoid having an inopportune quote being picked up and spotlighted as the defining moment of the debates.

The media focus on the gaffe as a defining feature of a campaign is well documented, both through academic articles on American presidential campaigns and through a quick look at the content generated over the course of recent presidential campaigns.

The First Great Gaffe

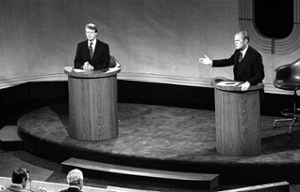

One of the first major examples of the “gaffe” in televised American presidential debates comes from the second debate between Carter and Ford in 1976, with Ford’s infamous statement that there was no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe.[1] This event captured several of the features discussed above, including the shift in public perception and discussion of the debate following media coverage. Although poll data showed Carter as holding a slight lead coming out of the debates[2], and while Carter took the opportunity during the debate to rebut Ford on the statement, he did not appear to share the incredulity of Frankel at Ford’s response at the time.

The Follow-Up

The initial media response to the debates was mixed, with the Soviet domination quote drawing a front-page article in the New York Times, but with the headline article on the debate focusing on other aspects of the debate, including fulfilling the Times’ expectations of prominent topics from the previous day.[3] Within two days of the debate, the Carter campaign began to focus on the statement, with Carter specifically citing “confusion”, “inaccessibility” and “’lack of knowledge’ about ethnic Americans” from Ford’s statement, demonstrating the tendency to extrapolate character traits and significant indications of leadership potentially (typically negative) from relatively small mistakes during the debates.[4] This ties into a wider academic argument surrounding image vs. substance as a part of the presidential campaign. As Parry-Giles has argued, despite the perception that an “issues-based” campaign is what the voters most want and is most beneficial to them, judgements of image are in fact valid, opening the possibility of viewing coverage of the gaffe as potentially beneficial.[5]

As the first television debate in sixteen years, this event began an electoral tradition that continues to this day. The Soviet blunder, which dominates public memory of the 1976 debates, may have contributed significantly to future strategies implemented for the debates. While the parallel development of the presidential debates and the "spin teams" surrounding them make it difficult to draw a cause-effect relationship between Ford in 1976 and future debate strategies, the clear focus for future presidential strategies was to script and control the debate environment as much as possible, including developing playbooks to establish pre-set answers to maintain consistency with other campaign materials.[6]

Contrary Perspectives

More recently, however, the focus on spoken missteps has come under scrutiny from academics, who argue that the net result of political punditry fixating on gaffes has been minimal, especially with the massive increase in information sources available to voters over the past ten years. Specifically, the campaign of Mike Huckabee in 2007 was often cited by pundits as being in the process of failure due to the candidates’ often extreme statements and lack of diplomacy dealing with the media, including right before Huckabee won the Iowa primary, which Greenwald argues indicates that voter responsiveness to pundit commentary may be significantly less than is commonly believed.[7]

[1] "Transcript of Foreign Affairs Debate between Ford and Carter." New York Times (1923-Current File), Oct 07, 1976. http://search.proquest.com/docview/122865581?accountid=13360.

[2] "Polls show More Viewers Rate Carter as Winner of 2nd Debate." New York Times (1923-Current File), Oct 08, 1976. http://search.proquest.com/docview/122822642?accountid=13360.

[3] "Ford-Carter Debate Tonight to Focus on Foreign Affairs." New York Times (1923-Current File), Oct 06, 1976. http://search.proquest.com/docview/122876729?accountid=13360.

[4] "Carter Assails Ford On ‘Serious Blunder’." New York Times (1923-Current File), Oct 08, 1976. http://search.proquest.com/docview/122758523?accountid=13360.

[5] Parry-Giles, Trevor. 2010. “Resisting a "treacherous Piety": Issues, Images, and Public Policy Deliberation in Presidential Campaigns”. Rhetoric and Public Affairs 13 (1). Michigan State University Press: 37–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41955590.

[6] Greenberg, David. 2009. “Torchlight Parades for the Television Age: The Presidential Debates as Political Ritual”. Daedalus 138 (2). The MIT Press: 6–19. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40543931.

[7] Greenwald, Glenn. 2008. “The Perilous Punditocracy”. The National Interest, no. 95. Center for the National Interest: 25–29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42896154.