Rocketmaker: the Boilermaker Who Built Purdue’s ‘Rocket Lab’

The world of American rocketry was not built in a day. In its infancy, it was made up of hundreds of thousands of the scientific community’s greatest minds. Some loomed large, like Chris Kraft and Wernher von Braun, while others history seems to have almost forgotten, though they might have maintained remarkably distinguished careers.

A Hidden Rocketeer

Michael Smith, a professor of history at Purdue University’s College of Liberal Arts, was reading an article one day about early rocketry in the US, which briefly mentioned something called a “Rocket Lab” at Purdue run by a man named Maurice Zucrow. Smith later set out to write an article about the mysterious rocketeer. However, when Smith found his resumes in Purdue’s archives, he saw Zucrow’s years of government service, work with the Research and Development Board (RDB) as one of America’s leading rocket engineers, and his time as a technical adviser on government, industry, and university committees.

“That was the clue about his big life,” Smith said.

With growing curiosity, Smith traveled to the National Archives in Washington, D.C. where he found Zucrow’s actual reports from the RDB, and then to the National Air and Space Museum Archives to seek out his many Aerojet Corporation reports.

“That was when I knew there was a book.”

Confident in the opportunity, Smith set out to write The Rocket Lab: Maurice Zucrow, Purdue University, and America's Race to Space, recently published by Purdue University Press, about the eponymous professor, the university, and its Rocket Lab, later renamed the Maurice J. Zucrow Laboratories.

Journey of a Jet-Setter

Maurice Joseph Zucrow, born in Ukraine in 1899, had a happy childhood in London. There, he boxed and earned high marks in school. He was close with his father, Solomon, who tutored him in math, reading, writing, and the Jewish faith. Zucrow moved to South Boston in 1915 where he worked odd jobs. He then served in the Army until the end of World War I and was admitted to Harvard in 1919.

After graduating from Harvard, Zucrow became interested in furthering his education at Purdue due to his fascination with cars and planes, along with the opportunity to study under the leading automotive engineer-scholar of the day, Harry Huebotter, who ran Purdue’s Internal Combustion Engine Laboratory while Zucrow was completing his graduate studies here. At Purdue, Zucrow’s long list of studies included mechanical engineering, hydraulic and industrial engineering, and mathematical physics and atomic physics.

It was at Purdue that he first became interested in jet propulsion. Here, he concentrated his studies on thermodynamics and fluid flows in internal-combustion and steam engines. In 1928, Zucrow was granted the first “earned” Ph.D. given out by Purdue, meaning that he completed both his studies and his research on our campus. Shortly after graduation, he decided to work as an internal combustion engineer and consultant in Chicago.

Things were looking up for Zucrow when the Great Depression hit. For a few years, he could not find a job, and trying to support a family made this all the more difficult to endure. After finally regaining employment, he worked on projects with industrial power plants, public utility companies, and the US Navy.

The work that Zucrow performed as a graduate student at Purdue made him stand out among his peers, helping him get a job with the Aerojet Corporation in 1943. At Aerojet, he served as lead engineer for novel rocketry projects, including rocket propulsion for early ballistic missiles and suborbital research rockets. He later served on the advisory committee for the Atlas rocket, which eventually launched John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth, into outer space.

“He and the other engineers on the committee deserve much of the credit, not just the Air Force brass who advanced it, and who take most of the praise,” said Smith.

The Propulsion Professor

In 1946, he returned to his original dream job: teaching at Purdue. Here, Zucrow taught the first university course in rocket and jet propulsion and wrote the jet industry’s first textbook, Principles of Jet Propulsion and Gas Turbines. According to Smith, Zucrow’s textbook and rising reputation was one of the reasons that Neil Armstrong chose to attend Purdue. Another textbook that Zucrow co-authored, Principles of Guided Missile Design, was featured in the popular movie October Sky which included an excerpt crucial to the character’s journey toward building rockets (Zucrow’s chapter titled “Fundamentals of Rocket Engines”).

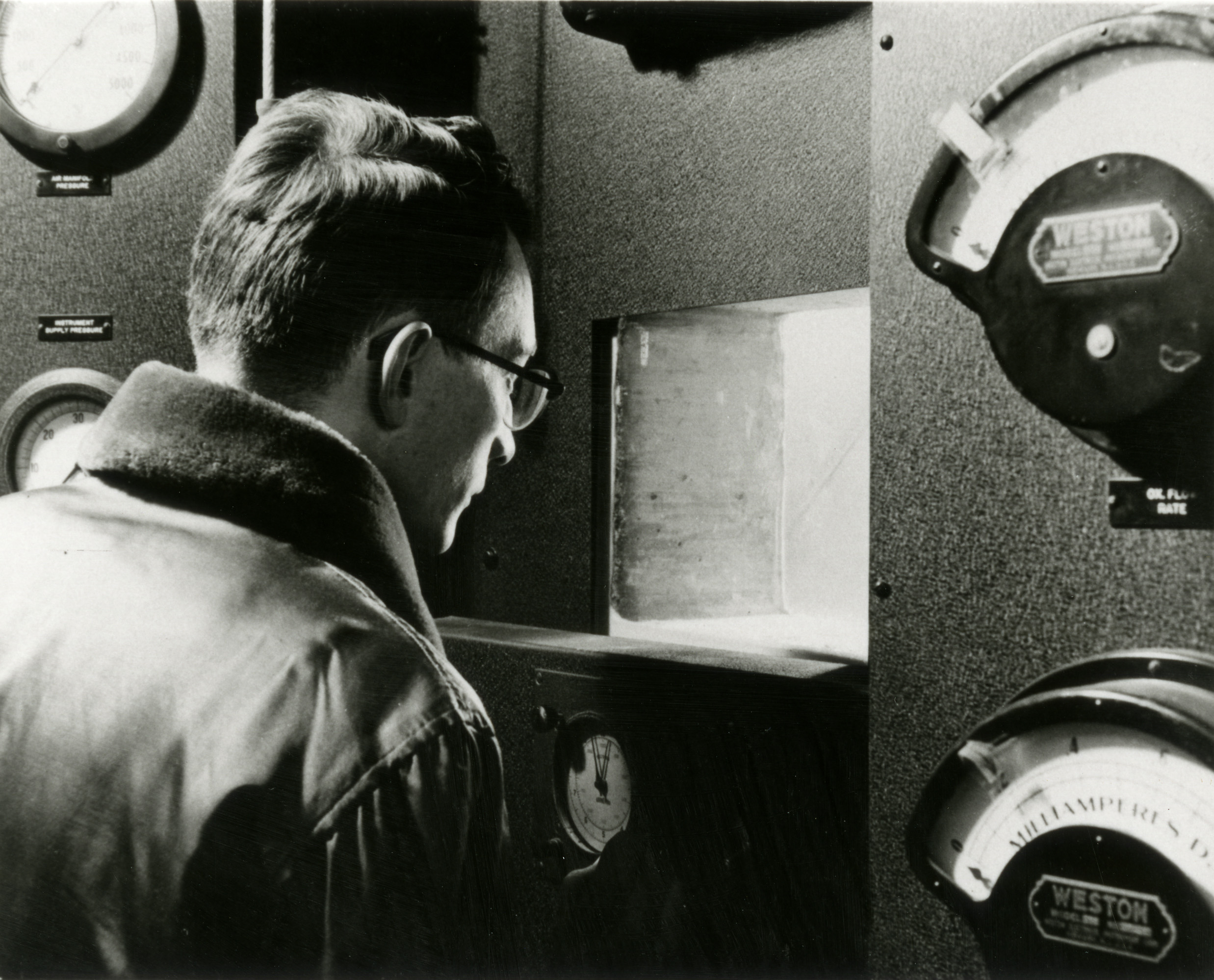

During this same year, he also began planning and building Purdue’s Rocket Lab. He was supported by Purdue President Frederick Hovde and funded by the US Navy’s Project Squid along with a grant from the US Air Force. Taking his experiences from Aerojet, he became a professor-teacher and educated his students on the challenges that designing and building jets and rockets posed. Princeton and Caltech were Purdue’s key rivals at this time; however, Zucrow’s team at Purdue was ahead in high-pressure combustion, later used in the Space Shuttle’s main engines—which never once failed a mission.

During Zucrow’s time at Purdue’s Rocket Lab, while great discoveries were being made, he could devote little time to his love of rocket research. He was constantly distracted by financial and business demands due to the lab’s construction and maintenance.

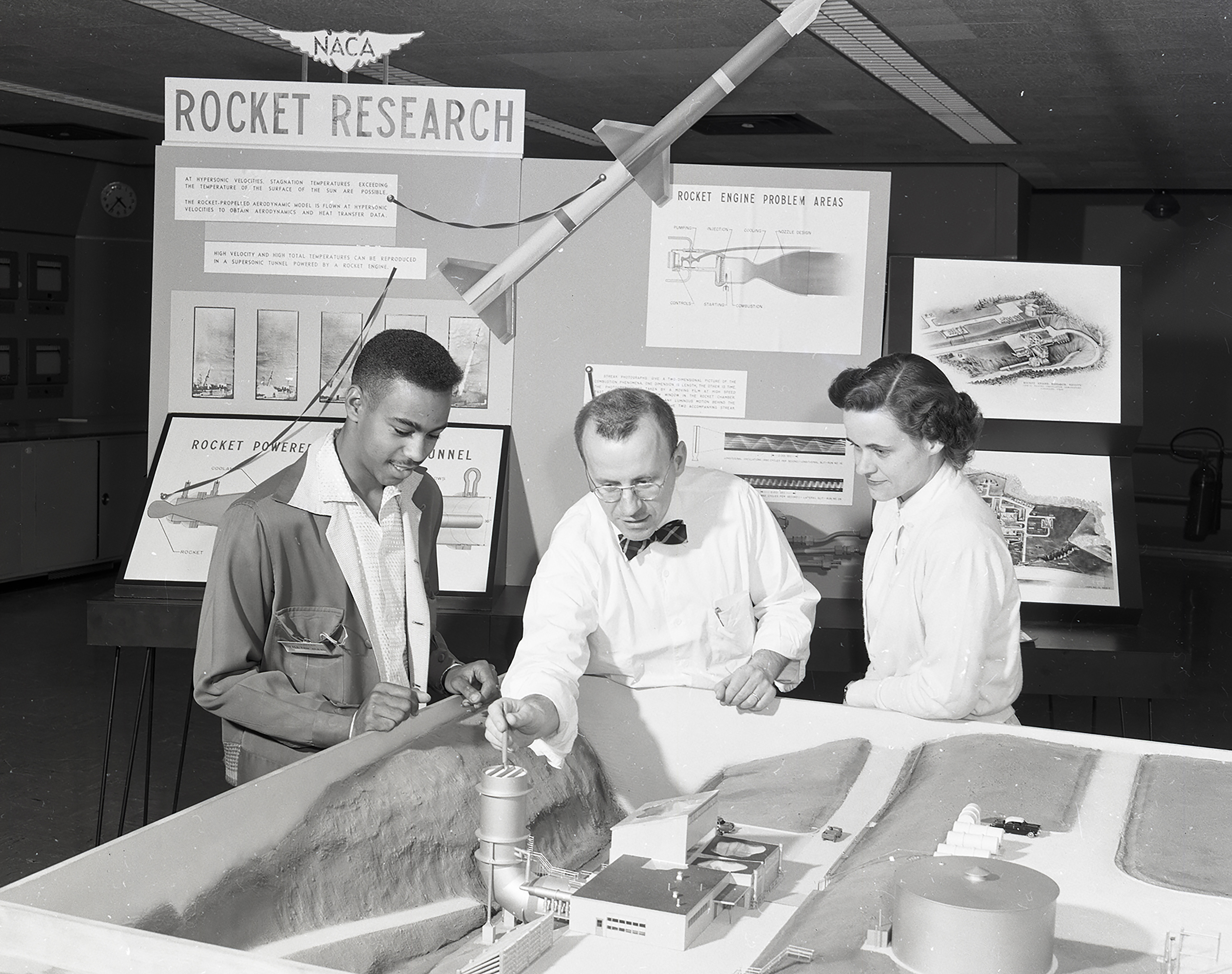

In 1952, Zucrow built a network of civilians and military personnel supportive of his initiative to establish a civilian agency that could launch rockets for peaceful space exploration, an agency like today’s National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). However, the leaders of the US Air Force and the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), NASA’s predecessor, rejected Zucrow’s idea.

“What a mistake,” Smith said. Had things been decided differently, he added, an American satellite might have been the first to orbit the Earth instead of the Russians’ Sputnik, which orbited in 1957.

In the 1960s, an aging Zucrow was a leading advocate for interplanetary exploration, and his students went on to do things like contribute to the development of the Saturn V, which took humankind to the moon and has been the most powerful rocket to successfully launch to date. J.P. Sellers, one of Zucrow’s students, helped improve and redesign the Saturn’s F-1 and J-2 rocket engines, used in its first and second stages. It is also worth mentioning that the F-1 rocket engine was one of the most powerful rocket engines to ever be used.

Skyward Legacy

As a teacher, Zucrow valued guidance. His laboratory was a support system that helped students learn on their own and overcome their mistakes. He cared for his students, securing jobs for many after graduation. He never spared them sharp, constructive criticism, however. Smith characterized Zucrow as, “outgoing but tough, compassionate and loyal,” and he valued excellent speaking and writing skills in his students.

While talking about his book, Smith reflected that, “Zucrow’s story is one of hard work and humility. He applied his own education to perfect his talents and share them with his teams of colleagues and students. Individuals mattered, sure. But the team more. For him and his engineers, only their contributions counted, from within the team and in service to industry, or the government, or the university. A contribution meant ‘from’ and ‘for’ the many, through the one. It’s a rule Zucrow shared with the other Purdue greats in the book: Hovde, Edward Elliott, Andrey Potter, Stan Meikle, and R.B. Stewart.”

Jerry Ross, Purdue alumnus and NASA astronaut, offered praise for Smith’s book. "’The Rocket Lab’ captures the excitement and optimism of the Apollo era when, as college students, we were able to study under the great pioneers, while eagerly looking forward to our own opportunities to be involved in the exploration of space."

Buy the book at: https://www.press.purdue.edu/9781612498416/

Learn more about the modern Maurice J. Zucrow Laboratories at: https://engineering.purdue.edu/Zucrow

Story edited by Taylor Frymier.