Lincoln-Douglas Historiography

The Debates and Lincoln

Lincoln as the "Great Emancipator"

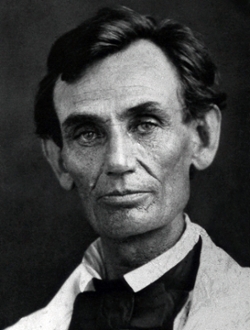

The Lincoln-Douglas debates are used as a viewpoint into the lives of the participants, particularly Lincoln, given his future fame. Some historians have focused on the apparent conflict between winning popular support for his policies and policy avowals on Lincoln's behalf that appear contrary to the modern view of Lincoln as the Great Emancipator. David Zarefsky discusses Lincoln's views on racial equality, including the Lincoln-Douglas debates as an example of the inconsistencies that his opponents also critiqued when they argued that Lincoln hedged his arguments to allow his statements to be read as hostile towards slavery by those who chose to read them such. At the same time, Lincoln retained a palpable appearance for potential voters in Illinois in 1858, many of whom "'took the inferiority of blacks for granted and supported the policy of excluding the Negro from Illinois, even as they did not support the possibility of slavery existing in Illinois itself.'"1 Zarefsky addresses that Lincoln's response to Douglas' charge that the founders had established the United States half free and half slave intentionally, and that Lincoln's arguments against this structure were contrary to their views.

This argument has an interesting contrast with the reaction of some abolitionists at the time, as well as from other modern historians. Lincoln's contemporaries based their arguments on the contrast between a more moderate anti-slavery position that rejected black equality, versus a policy that not only abolished slavery, but also provided legal and social equality for freed slaves post-abolition. One of the most prominent advocates of the latter perspective was William Lloyd Garrison. The vocal abolitionist published selected excerpts from Lincoln's debates with Douglas to demonstrate to prominent supporters of abolition how Lincoln lacked of genuine egalitarian principles.2 From his 1959 article on the debates, Fehrenbacher argues the opposite point of view as well, that Lincoln's answers were not hedged or evasive, "unless evasion be defined as a forthright answer which in time ceases to be acceptable".3

2"MR. LINCOLN AND THE COLORED FOLKS." Liberator (1831-1865) 30, no. 34 (Aug 24, 1860).

Stephen Douglas

Changing Perspectives on the “Other Man” in the Debates

With Lincoln ascending to the presidency and historical immortality in 1860, the popular narrative often neglects Stephen Douglas. He appears as the man who won the battle in the debates, but lost the war in the presidential election two years later. The ways that historians have discussed Douglas has evolved significantly over the century and a half since the debates, bringing a more nuanced view of both Douglas and the events leading up to the American Civil War that he influenced.

1880’s - In the decades immediately following the war, Douglas was not popular either with historians in the North or the South, and historians overwhelmingly characterized Douglas as the “’great failure’”. This attitude was exemplified by the exclusion of Douglas from the American Statesmen biography series in the 1880’s.

1900’s - One viewpoint popular before the First World War was to focus on Douglas as a proponent of Western expansion, seeing his popular sovereignty doctrine as an attempt to push the issue of slavery back under the rug to allow the nation to return to the business of expansion. In this interpretation, the 1858 debates would have been a further attempt to popularize this doctrine, while responding to criticism of it.

1920’s - As part of a wider revision of historian’s views of the American Civil War during the 1920's, scholars moved away from studying the issues such as Douglas' stance on popular sovereignty that led to the war. This viewpoint sought economic and cultural causes for the clash between North and South. Douglas' role in pre-war politics was characterized as rational and concilatory, but ultimately futile.

1980’s - The decline of this view through the more recent research of historians such as James McPherson should force a revision of its applicability to Douglas as well through the impossibility of reconciling his attempt at compromise with hardline views on slavery either North or South.