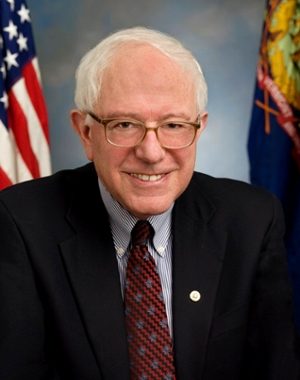

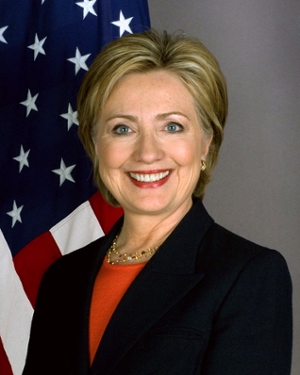

The Underdog: Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton

The 2016 Democratic primary is demonstrating the power of the underdog candidate against a larger, wealthier, and better established organization, in the contest between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders for the Democratic nomination, with the primary debates at the heart of the conflict. While the scrum of candidates across the aisle wage a fourteen (or more)-way struggle for dominance, the Democratic field has come down to two major candidates (with Martin O’Malley dropping to a distant third in recent polls). While Clinton’s name recognition, extensive record, and well-entrenched political machine would seem to make her the dominant candidate over the junior senator from Vermont, these same qualities make Clinton unpalatable to many within her own party, as well as many independents, who see her record as tying her down and her insider status in Washington making her a symbol of the “establishment” which is less that popular with American voters. In this field, despite having a lower public profile than Clinton, Sanders has the potential to win the Democratic nomination as a candidate without extensive connections to Washington, who proposes more sweeping solutions, as well as appealing to the party’s base. The underdog candidate is a recurring phenomenon in American presidential politics, across both political parties, and the parallels to past campaigns demonstrate the effectiveness of utilizing a public forum to overcome a disadvantage in fame and financing. Whatever Clinton’s strategy may be in the coming months, the one mistake she cannot afford to make is underestimating the power of an underdog candidate to unseat the establishment candidate.

The 1960 Democratic nomination process demonstrate the process by which a lesser-known, politically unseasoned John F. Kennedy could successfully challenge the dominant Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson for the Democratic nomination that Johnson believed was guaranteed to be his. While there were no primary debates in 1960, the equivalent public forums were the primary elections, still a relatively new innovation. With only fourteen states holding primaries in 1960, Johnson believed that he could trust in the machinations of the party bosses at the national convention, and his established public prominence as Senate Majority Leader, to bring him the nomination, and thus chose not to campaign in the primaries at all. However, Kennedy’s drive across the country brought him national recognition as a serious contender for the presidency, and when the convention rolled around, the combination of delegates committed to Kennedy by their primaries and the prominence of the organization he had built during the primary campaign was enough to bring Kennedy the nomination. During the general election, the first U.S. presidential debates, televised to a national audience, gave Kennedy a chance to demonstrate his stature against his highly visible opponent, Richard Nixon, who as Vice President had previously established himself in the national arena in the same way Johnson had. The ability to appear on the same stage as Nixon, and to give and take with him at all, gave Kennedy a credibility boost which contributed to his victory in the general election. The parallels between 1960 and 2016 are not perfect; even as the less-recognized candidate, Kennedy was still the inheritor of an extremely potent political organization in Massachusetts politics, which he expanded to great effect during the election. However, the 1960 election still represents an example of utilizing a public format to bring a previously unknown candidate into national prominence.

Thus far, the 2016 Democratic debates have been closely contested between Sander snad Clinton. However, the debates may be benefitting Sanders in the long run. Although Clinton was reported as the “winner” of the first debate by most polls, the results of the 11/14 debate showed Sanders as the winner, with several of the features highlighted by the debates bringing attention to aspects of Clinton’s campaign that may be less attractive to voters over the next year, such as her attempt to defend massive campaign donations from Wall Street by invoking the 9/11 terrorist attacks. These gains demonstrate the value of appearing before the nation in a public forum to bolster a candidate’s stature against a better-known opponent. If Sanders can leverage the capital he has earned with the public into a larger, stronger organization, he has a chance to make his own underdog story over the next year.