Laura Anne Fry: An artistic legacy

Ancestor discusses influential pottery designer and ceramicist’s life and career as Purdue faculty member

From 1890 until she retired in 1922, Laura Anne Fry developed an arts curriculum that, as Judith Vale Newton and Carol Ann Weiss assert in "Skirting the Issue: Stories of Indiana’s Historical Women Artists," attracted “so many students to the art department and the university as a whole that [Purdue’s] enrollment outnumbered their primary in-state competition, Indiana University.”

A ceramicist, woodcarver, chemist, and entrepreneur who designed pottery for Rookwood in Cincinnati prior to arriving at Purdue, Fry taught Boilermakers when the Arts and Crafts Movement – and American Art Pottery especially – reached the zenith of international renown.

“The fashion for art pottery lasted just a short while – from the 1870s until just after World War I – but it became so popular that it was manufactured in the United States. Several serious and innovative potteries were founded in that period, the largest and most famous of which was the Rookwood Pottery of Cincinnati,” noted Carol Prisant in "Antiques Roadshow Primer."

Together with St. Louis’ Scott Joplin ragtime piano, Chicago publisher and editor Harriet Monroe’s "Poetry: A Magazine of Verse," Frank Lloyd Wright’s prairie homes, Louis Sullivan’s steel-frame skyscrapers in Chicago and St. Louis, and Wisconsin-born Gustav Stickley’s Mission-style furniture, Rookwood ceramics placed Midwestern culture on the world stage in the late 19th and early 20th century.

As we celebrate our sesquicentennial, it is appropriate to remember Laura Anne Fry, a prominent artist and faculty member when Purdue was young. To learn more about her life and work, I contacted Laura F. Fry. Besides her role as senior curator of art at Tulsa’s Gilcrease Museum, and author of a master’s thesis on Laura Anne, Laura F. Fry is also the great-great niece of her namesake and her family’s unofficial historian.

Q: Please respond to the following passage about your ancestor that appeared in Robert W. Topping’s "A Century and Beyond: The History of Purdue":

Another early faculty member in the [Purdue President Winthrop E.] Stone administration was Professor Laura Anne Fry. Though she had none of the conventional degrees, Professor Fry was an extremely talented New Yorker who had been a pupil of William H. Fry in wood carving, William Chase in painting, Kenyon Cox in drawing, and Lewis T. Rebisso in sculpture. She lived in Ladies Hall, the name given to what had been known originally as the Boarding Hall and what had become essentially the woman students’ residence.

Why do Purdue histories emphasize Laura Anne Fry’s training with male artists, and why is Fry incorrectly listed as a “New Yorker?”

A: In 1890, Laura Anne Fry became a professor of industrial arts at Purdue University. She was 33 years old, a leading American ceramic artist, inventor, and teacher. She had helped found the

American Art Pottery movement in Cincinnati in the 1880s, had shown her artwork in national exhibitions, and had earned a U.S. Patent for a new spray technique of applying glaze colors to pottery.

Fry was a successful professional artist in an era when women were actively discouraged from pursuing any profession at all. However, Fry’s art career also laid bare the gender biases of the late 19th century. Through personal experience, she fully understood that American society tended to value men’s work far more than work by women, and as a result, Fry became a fierce advocate for her fellow women artists.

Although she had no formal college degree, Fry’s varied training and professional experience qualified her to teach at a university level. While she had studied art with several female artists and started her art career in Cincinnati, in Purdue’s "Debris" yearbook Fry instead listed her training with male artists and noted her membership with the Art Students’ League of New York – perhaps recognizing that these qualifications would earn greater respect from the academic community.

As a result, a Purdue historian in 1988 incorrectly assumed that Fry was a “New Yorker” when, in fact, she was born in Indiana and spent the vast majority of her life and career in Indiana and Ohio. Today, I hope to set the record straight for my own great-great aunt and namesake.

Q: What role did Laura Anne Fry’s family play in fostering her arts training and supporting her art career?

A: Like many women artists from across Western art history, Laura Anne Fry was first introduced to art through her family. Her father, William Henry Fry, and grandfather, Henry Lindley Fry, provided her earliest artistic training and encouraged Fry to pursue a professional career.

Henry and William were both trained as woodworkers and cabinet-makers in England, and both embraced social reform issues and were members of the Swedenborgian Church – a noted denomination for many 19th-century intellectuals. They emigrated from England to Cincinnati in 1850, where they established a woodcarving studio and eventually a woodcarving school in the 1870s.

Most of their students were women, and the Frys actively supported women’s rights in the late 19th century.

Laura’s family recognized and encouraged her early artistic talent. Her father and grandfather trained her in woodcarving, following design principles established by the English Arts & Crafts Movement – seeking inspiration in the natural world and in a variety of historical styles, and prizing hand craftsmanship over industrial mass production.

Although she had nine siblings, she became the only one to pursue a professional career in the arts with the full support of her father and grandfather.

Q: Laura, your namesake led the industrial art department at Purdue when the Arts and Crafts Movement and the American Art Pottery movement were at the height of their national and international prominence. Why were decorative arts products (such as Rookwood Pottery) a critical element of the Arts and Crafts Movement? How did women artists affect the Arts and Crafts Movement, and how did 19th-century understandings of gender roles affect Fry’s art career in particular?

A: If I may, I’ve never liked the term “decorative arts” because it sounds so insubstantial – it devalues art that was traditionally made by women and is a very Euro-centric concept. Artists in other areas of the world generally do not draw a hierarchical distinction between painting and ceramics, for example. However, the term remains commonly used today to refer to “utilitarian” works including ceramics, woodworking, silver, glass, and textiles.

The Arts & Crafts Movement initially emerged in England and the United States in the late 19th century as a response to the increasing industrialization and uniform mass-production of modern life. Rapid industrial growth gave rise to crowded, unsanitary boomtowns with poor living standards – a familiar setting from Charles Dickens’ novels.

As a reaction against the negative impacts of industrialization, Arts & Crafts leaders such as William Morris in England encouraged a return to creating individually handcrafted household products – today often referred to as “decorative arts.” Morris promoted handcrafted items as a positive influence on society, a means for arts to contribute to fulfilling, everyday work.

Many Arts & Crafts makers were women, some creating items for their own households and some forging incomes and careers working with textiles, metalsmithing, ceramics, and other media.

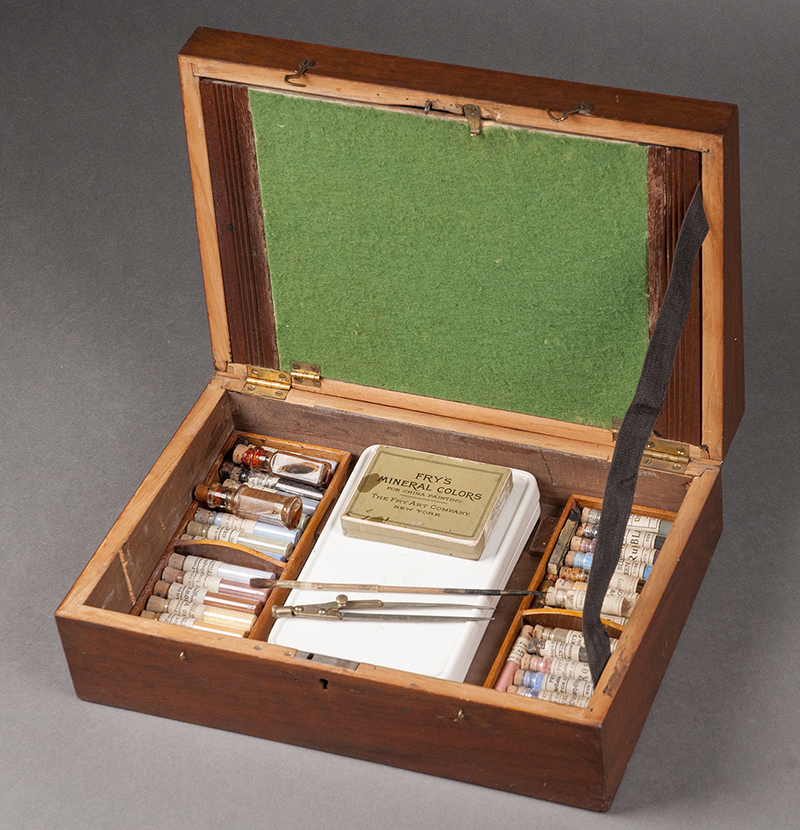

In the United States, small pottery companies like Rookwood Pottery in Cincinnati followed the ideals of the Arts & Crafts Movement and emphasized the handcrafted, individual creativity of each item – inviting artists to sign each piece and promoting their pottery as a high art form. Laura Anne Fry became one of the earliest employees of Rookwood in 1881.

While most women in the studio were employed as pottery decorators, Fry also experimented with new glazing techniques and ultimately invented a new method of spraying underglaze colors on pottery with an atomizer. Her male supervisors initially scoffed at her invention – but nevertheless she persisted.

In the end, Fry’s atomizer technique provided Rookwood with new blended colors that helped propel the pottery to international fame at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris. That same year, she was awarded a U.S. Patent for an “Improvement in the Art of Decorating Pottery-Ware.”

While Fry’s invention undoubtedly contributed to Rookwood’s rise to fame and increased profitability, the manager of Rookwood Pottery was reluctant to recognize her distinct impact on the pottery’s success. He refused to honor Fry’s patent, and, in 1892, she sued Rookwood Pottery for patent infringement. The lawsuit split the Cincinnati art community in two, with several prominent artists, art dealers, and museums taking sides in a debate around the business of art.

None other than Judge William Howard Taft issued a final opinion in the case in 1898 – in Rookwood’s favor. Fry had fought for years to protect her idea, likely hoping that licensing her patented invention could contribute to her income and potentially give her the means to begin her own studio.

Perhaps in response to her own struggles for credit and professional recognition, Fry continued to avidly support other female artists. In her writings and public lectures, she championed women who spearheaded new developments and experiments in American ceramics, raising amateur “decorative arts” into a professional art form.

Q: How does Laura Anne Fry’s legacy of working with Rookwood and American ceramics resonate today?

A: In tandem with other ceramics artists in the late 19th century, Fry’s efforts to raise pottery to a high art form helped influence the founding of the earliest university programs for ceramic arts in the United States in the 1890s. Today, spray booths can be found in any well-equipped ceramic studio, and many contemporary ceramic artists continue to utilize a similar technique to Fry’s patented “improvement” in decorating pottery.

Fry’s efforts to support her fellow artists continue to impact the Lafayette community. In 1909, she led the founding of the Lafayette Art Association to provide a venue to exhibit and collect work by local and regional artists. She led the organization until 1924, and it became the basis for the Art Museum of Greater Lafayette.

Like many women today, Fry simply sought equal recognition for her work. Her struggle to earn recognition for her own ideas continues to resonate, as women still strive to earn equal pay for equal work, and for equal representation in leadership roles throughout education, business, government, and the arts.