Meet visiting artist Anna Ridler

Artist's digital tulips draw historical connection to cryptocurrency craze

Once upon a time in the Netherlands, people were willing to spend astronomical sums of money on tulip bulbs.

The “tulip mania” that swept through Europe in the 17th century is often referred to as the first recorded speculative bubble, where the going rate for a good far exceeds its fundamental value. But while “tulip mania” might have been the first example of this spending phenomenon, it was far from the last.

London-based artist Anna Ridler sees a behavioral similarity between what happened with Dutch tulip prices nearly 400 years ago and the wild fluctuations in cryptocurrency prices in recent years. That similarity served as the inspiration for her artificial intelligence-driven installation, Mosaic Virus, the centerpiece of her "Dreaming, Automated: Deep Learning, Data Sets, and Decay" exhibition that opened this week at Robert L. Ringel Gallery in the Stewart Center.

The exhibit, which will be open from Aug. 19 through Sept. 27, allows visitors to see digitized tulips thrive and wilt before their eyes, with the current price of bitcoin driving the stages of growth that the onscreen tulips display.

It was an ambitious digital project, with Ridler collecting images of approximately 10,000 tulips to construct the data set upon which "Mosaic Virus" is based. Some AI-driven artwork might require very little actual art from a human programmer, but this is not one of those pieces. Ridler makes it clear that what gallery visitors will see in "Mosaic Virus" is her specific vision, and that the AI-driven changes that the piece features occur intentionally – not by chance.

Ridler – who will visit Purdue in September to lecture, meet with students, and attend the exhibition’s Sept. 26 reception – spoke recently with THiNK Magazine editor David Ching about her artwork. Here are excerpts from that conversation:

Q: I understand that within the art community there is a conversation about AI and other digital art where some question what is the artist’s work and what is the work of the technology. As an artist who works within the field, where do you stand on that?

A: I think it is different for different artists. I think different artists use AI and machine learning in different ways. There is a spectrum of who is an artist and where the machine is doing the artist’s work. To me, the way that I tend to use it, I’m very much like, ‘This is my work. I am the artist and I’m using AI and machine learning like a tool and a process.’ I am making all the decisions and the decisions I’m not making are a very conscious choice, to allow this element of chance to emerge in the work. So in a way it’s all quite pre-planned to a certain extent.

With the tulip project, knew very much the type of thing that I wanted to make before I made it, which meant that I then had to create the data set, I had to work with the algorithms. Obviously I could never predict what the actual video output would be like, but I still had a vision of what I wanted it to look like. So for me, there’s a huge amount of control and that makes it an art project.

For me, there are lots of really interesting things about how machine learning works. It makes me able to add pullouts and concepts in the piece. I thought heavily about that, as well, thinking about how it works and what it does in order to make a work rather than just being, ‘Oh yeah, it’s cool. It’s the thing that everyone wants now.’ So both of those things mean that to me there’s a very heavy authorship in the work.

Q: And the amount of legwork that goes into creating the data set is remarkable. How many photos of tulips are there?

A: There’s 10,000 tulips, and that’s a really heavy amount of tulips to come about in the Netherlands. When you think about artificial intelligence, and it works when you’re talking about digital work more broadly, sometimes there’s this assumption that, ‘Well, it’s very easy to remember that all of the things that make up digital worlds – particularly machine learning – at some point started off in the real world.’ So you always have to have a data set, and at some point the data set was an object on someone’s desk that they took a photo of. It’s sometimes really hard to remember that. But for me, I was going all over the Netherlands buying these tulips, trying to find the variety and trying to find striking ones, that it brought home that I needed to find these real objects in order to then create artificial ones.

Q: At first glance, it seems wild to tie the metamorphosis of the tulips in your work to the price of cryptocurrency. But then it makes sense when you learn a bit about the history of tulip mania and how these two speculative bubbles are actually similar. What inspired you to compare them?

A: You’ve got tulip mania and you’ve got cryptocurrency mania, but you’ve also got a mania around AI, as well. That’s the other thing, that AI and machine learning is inside its own speculative bubble at the moment. So the material that I’m using is echoing the subject matter in a way.

Q: When you correlate these speculative bubbles, what do you want people to consider when they see your work?

A: That is hard. Some people see it and just see it as a very beautiful moving-image piece of some flowers. One of the things I’ve always been interested in is how you can take something quite simple and then telescope into it and start to uncover all of these interesting, hidden things. I think the more people understand how it’s been made and what goes into it and the different kind of connections, the more that they start to think about the fragility of these systems and start to make these connections.

One of the other huge references in this piece was Dutch still-life painting, which has its own particular language and grammar with things that are in it. Dutch still-life paintings are these really incredibly beautiful, floral bouquets against a background that were really, really popular in the 17th century while tulip mania was happening. They are part of a traditional painting called vanitas paintings, where painters would paint these really beautiful realistic flowers. A thing about them is that flowers die and people looking at these paintings would understand the fragility and shortness of life. And I suppose in a way, even if you don’t understand anything about bitcoin or tulip mania, there still is this tradition of flowers in art history, which might get people to start thinking about these ideas, as well.

Q: The fact that people would attach this incredible value to what many of us would consider a frivolous item is pretty remarkable.

A: I know, it’s insane. But then even now, people are paying insane amounts of money for CryptoKitties and stuff like that. It’s just this weird thing that people want to spend huge amounts of money on what are status symbols. It’s really insane.

Q: Maybe that says something about vanity or some other human condition?

A: I think it does, and this is something that I’m also quite interested in in my work: finding these connections between what might seem like very distant points in time, like 17th century Holland and what’s going on in the tech industry now. I think when you start talking about things where there’s enough of a distance to see how mad it is, you kind of get people to engage with those kinds of ideas around madness whereas if you talk about things in the now, sometimes it’s so heated that people can’t really understand what’s going on.

Q: What will people see when they come to the exhibit at Purdue?

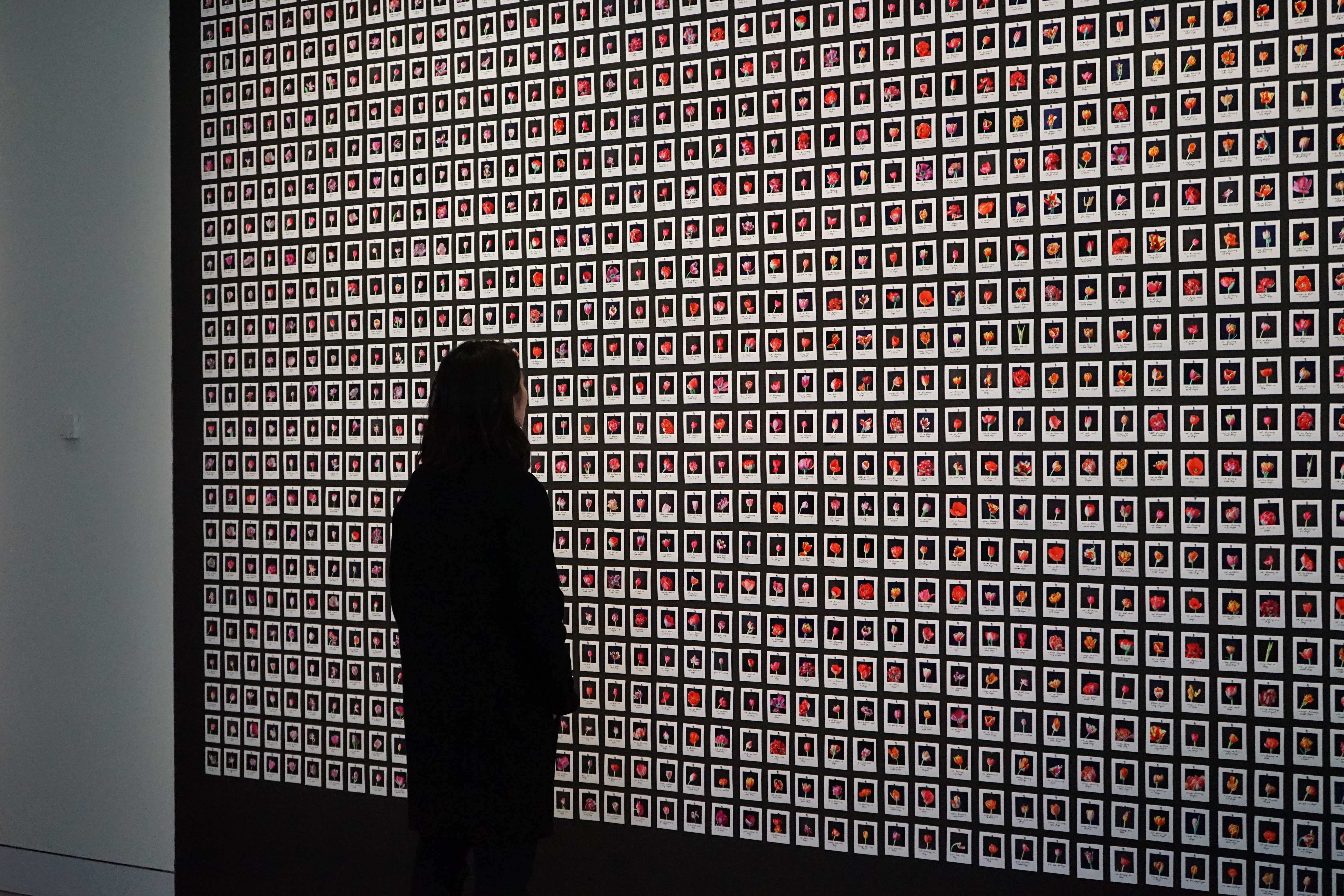

A: There’s going to be two series of works. It’s going to be the tulip work, "Mosaic Virus," which we’ve already talked about. And then there is going to be part of the data set. The full-on 10,000 tulips [a piece titled "Myriad (Tulips)"] is about 100 square meters, so this is just going to be a tiny part of it. I think there’s around maybe 1,000, maybe less, that I’ve sent over. Just a one-wall thing. Another project that I did, which was a very early [attempt at] trying to work with machine learning as an artistic tool, was called "The Fall of the House of Usher," where I trained a neural net on how I draw and then used that to produce an animation.