The OWL at 25: The Future

How will writing instruction change in the future?

Dave Taylor had the foresight to understand why it would be useful to create an online home for the Purdue Writing Lab’s instructional handouts before most folks even understood that the World Wide Web existed.

But even Taylor would have struggled to predict how technological advancements would change things in the 25 years since he and former Writing Lab director Mickey Harris founded Purdue’s renowned Online Writing Lab (OWL) in 1994.

“All the way back then, we were looking at the internet as a way to publish content, but not as a way to connect a million different things,” said Taylor, a Purdue graduate student when he developed the initial version of the OWL. “The idea that I have about 40 smart devices in my house that are online at all times, it’s kind of crazy. It’s not something I ever would have anticipated.”

It seems equally mind-blowing to imagine how future advances might further change the OWL and the processes involved in all online writing instruction.

The OWL already has an active multimedia presence, with nearly 22,000 subscribers to a YouTube page that features dozens of instructional videos. These quick, clever clips represent one example of how today’s users engage with OWL content in different ways than they did in years past.

“I think one of the major ways it has changed is trying to respond to a different type of internet use,” said Kaden Milliren, an English M.A. student and OWL contributor. “Why would a student read something that might take 10 minutes to read when they can watch a five-minute video on YouTube where they can get the same information and it’s more entertaining that way? We see some obvious changes in the format and genre of how this information is disseminated.”

Next steps

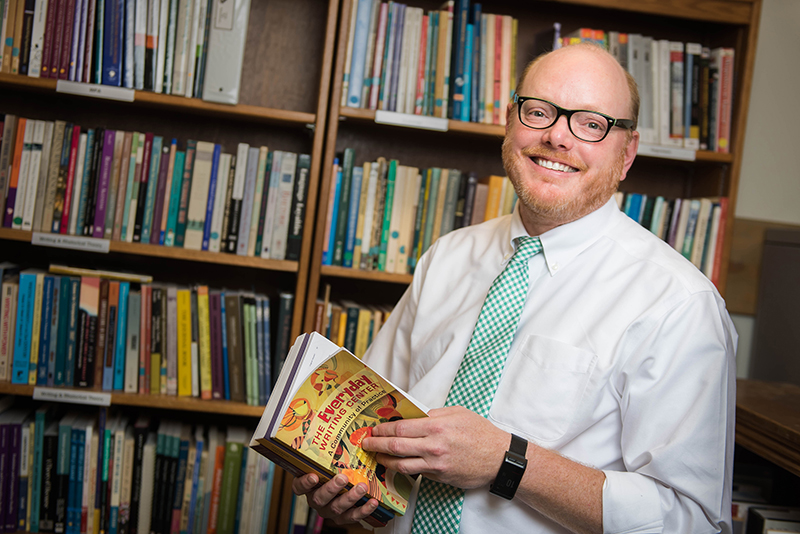

What might be the next evolutionary steps for the OWL?Will virtual e-tutoring replace the in-person interaction that takes place in physical writing centers? Writing Lab/OWL director Harry Denny pointed out that online tutoring – even with increasingly sophisticated video conferencing technology – is not the most effective solution for some Purdue students, creating uncertainty about how to optimize writing center resources.

“We are getting increasing pressure to do more and more e-tutoring and online tutoring, but also to develop resources to help other colleges with that,” said Denny, an associate professor of English. “But you still have a significant population, both among our staff and on campus, that just want face-to-face. Alternatively we have a huge multilingual population who are never served well by trying to get some of their issues addressed by e-tutoring.

“We feel this tug and pull around how we reach people in the best ways that are pedagogically sound for tutoring and writing versus how we deliver our content.”

Delivering that content is also more complicated than one might expect. The OWL and its graduate student researchers have long been concerned with accessibility issues, and those concerns remain even in today’s increasingly connected world.

The OWL generates millions of clicks overseas – and even here in Indiana – from users on dialup connections. Denny and his staff must consider these users’ needs with every new element they add to the OWL site. A page loaded with graphics and other visual material typically takes longer to load, thereby reducing the quality of a dialup user’s interaction with the site.

“I think there’s this misunderstanding that everybody has access to the internet. Yet in the county where I live, 50% of the community does not have high-speed internet and they’re still on dialup, which is hard to believe,” said former OWL webmaster Dana Driscoll, an associate professor of English at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. “And so I think that we’re going to think about what online writing instruction looks like from sort of a democratic standpoint, from an access standpoint.”

Opportunities to connect

Nonetheless, as connectivity expands, so too do the possibilities for online interaction. Former OWL researcher Jaclyn Wells – now director of the University Writing Center and assistant professor of English at the University of Alabama at Birmingham – imagines a future where beyond serving as repositories for citation instructions and writing handouts, online writing centers will be able to easily facilitate direct communication between instructors and those in need of assistance.“It’s always nice when students tell me, ‘This is what I’m really struggling with. This is where I really need you,’ ” Wells said, citing the question-and-answer interactivity on the APA Style Blog as a potential model. “And so it would be great to see more online resources that have students really engaging and telling us what they need so that we can then create it.”

Writing instructors’ concern is that ever-improving artificial intelligence technology will become something akin to Frankenstein’s monster, functioning beyond the control of its creator. Will automated writing correction and revision engines – like the software under development at OWL partner Chegg, Inc. – advance to the point that the program, not the writer, is actually producing the written piece?

“That’s what keeps us up at night,” said former OWL coordinator Allen Brizee, associate professor of writing at Loyola University Maryland. “It’s kind of terrifying.”

Indeed, it should terrify writing instructors that a software program could be given a set of parameters and churn out a paper without any further assistance from a student. Academic writing should represent an individual’s grasp of the subject matter, so automating the writing process would reduce, if not eliminate, the intellectual growth that occurs during this extremely personal exercise. Never mind the damage it would do to writers’ critical abilities to express themselves via the written word.

“I feel like teaching a technology to understand the human aspects of language like metaphor and narrative would be like teaching it to breathe or to sing,” Milliren said. “I don’t know if it’s capable of doing that, but probably it is.”

Future innovation

Not just yet.The OWL team has collaborated with Chegg as it develops its grammar checker, challenging the company to think more dynamically about the writing resources it provides. Denny’s sense is that while AI-driven composition remains on the horizon, it is not yet ready to replace direct human involvement in the traditional writing process.

“I would love to see us use this partnership to support us, and that might be learning how to do better online tutoring,” Denny said. “We have students who need writing support 24/7, and I just don’t have tutors around 24/7. Is there a way in which the OWL can be interactive in terms of how we do our pedagogy really well? Maybe that’s on the horizon with their grammar-checking software, but I don’t see a level of sophistication around writing that our clients need on this campus. I could be wrong about that, but I don’t see that happening anytime soon.”

Driscoll pointed out that even if technology eventually helps some students cut corners on written assignments, writing instructors can also take heart in the knowledge that it will never replace the need for one-on-one interaction with those who want to learn to express themselves effectively.

For Harris, who established the Purdue Writing Lab in 1976, nearly two decades before the OWL came into existence, personal interaction must always remain at the center of core writing center efforts, no matter how technology changes the delivery of service.

“There is so much on the website that may or may not be understood by the person that in a conversation sitting at a tutoring table, I can help that student,” Harris said. “For example, their punctuation or a typo, a simple thing where it says to put a comma between independent clauses with a coordinating conjunction. What does that mean to that student? Does he know what a sentence is? Does he know what an independent sentence is? Does he know what a coordinating conjunction is? Do we look at it in his own writing and try to find examples of what they might want? So it’s a resource, but it can’t answer questions that require further clarification.

"When I call it a resource, that’s exactly what it is. There’s an awful lot of information that people may need and use, but I hope it never replaces the need for interaction between humans to talk about writing.”

FUTURE OF THE OWL AND ONLINE WRITING INSTRUCTION

Current and former OWL leaders and contributors share their thoughts on how technological advances might change the site in the future:“There are many writing centers that have video conferencing. Some of them are synchronous, some of them are asynchronous, where students send in papers and written feedback comes back, which I think is not good interaction. It’s not instant and it’s not clarifying because it’s always in writing. So much is dependent on tone of voice and all the non-verbal communication that is going on with human interaction. But there are all types of software out there that allows conferencing in so many different ways that are very sophisticated.” – MICKEY HARRIS, professor emerita of English and founder of the Purdue Writing Lab and OWL

“As technology has changed things, the act of writing, the act of composing on the page, the act of a tutor working with a writer, those haven’t changed all that much. And so we kind of have that set of best practices that might be translated with new technologies. But in the end, talking one-on-one with writers, which is what the writing center does, or serving materials to writers, the format might change, but some of those core practices stay.” – DANA DRISCOLL, associate professor of English at Indiana University of Pennsylvania and former OWL webmaster

“It’s hard to speculate about 25 years from now. It would be interesting to see what they can do with online instruction now that we have all this VR technology. Are we going to be able to have virtual classrooms and virtual tutoring sessions? That would be interesting.” – JEFFREY BACHA, associate professor of English at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and former OWL webmaster

“I think our next frontier is thinking about how do we continue to be more and more user aware and what that might look like in a variety of ways, whether it’s questions of bandwidth, whether it’s how do we help explain principles about academic English to audiences in other language cultures and what that might look like. There’s a lot of conversation in composition circles about what it might mean to be multilingual or translingual and how might that challenge us to complicate what we’re saying about language in any number of ways.” – HARRY DENNY, director of the Purdue Writing Lab/OWL and associate professor of English

“I would love it if we could figure out a way that we had some sort of app or widget tied into the OWL that would help people navigate it better. You start searching for something on the OWL and the OWL sort of talks back to you. I think they have that on some pages, but my sense is that that’s all about suggestive selling. I haven’t seen anything robust coming down the pike that we could immediately take advantage of.” – HARRY DENNY

“I wonder if there’s going to be some technology, whether it’s in our lifetimes or not, that will make the OWL and adjacent websites obsolete – that there’s going to be some technology that means that nobody has to go and look for these types of resources. They can just discuss it with some sort of artificial intelligence.” – KADEN MILLIREN, OWL contributor and current M.A. student in Rhetoric and Composition

“The not-so-great path that Rhet/Comp tech writing people are concerned about is over automating writing instruction in online platforms. Writing correction engines and revision engines and grading engines are pretty sophisticated, but I don’t think they’re ever going to completely replace somebody, a human being, reading a piece of writing, either synchronously or asynchronously, over audio or video link, and providing feedback for somebody. Even if that happens where somebody submits the paper and then somebody reads it and comments on it and then returns it.” – ALLEN BRIZEE, associate professor of writing at Loyola University Maryland and former OWL coordinator

“A big thing in writing pedagogy today is writing across disciplines, so how do we think about writing in specific disciplines versus trying to achieve some universal writing that doesn’t really exist? And if we’re thinking more innovatively, I’m sure they would like to find a way to have it be a little more interactive so that you’re not just reading resources that link to other resources and just passively absorbing it, but some other way to do more interactive, finding a way to share your writing and connect with tutors who could comment on it. The Writing Lab at Purdue is moving into that a little bit where they’re trying to do a little more digital stuff so that you don’t have to come into the physical Writing Lab necessarily.” – KYLIE REGAN, OWL contributor and current Ph.D. candidate at Purdue

“From a content development perspective, I think the OWL needs to continue staying ahead of the curve on the different composing scenarios that all people engage in. This means continuing to develop content that centers on composing across different kinds of media.” – FERNANDO SANCHEZ, assistant professor of English at University of St. Thomas and former OWL webmaster

“There are things on the webpage that are not changing all that much: our resources for articles, idioms, commas, prepositions. A lot of functions of grammar aren’t terribly changing all that much, so we can do more video with that, but some of the things that we are developing video content for, I get a little nervous about how quickly will that look dated. At what point will our tutors look like they’re speaking from the 1950s? How do you update that? Most of our video content we’re having to reshoot so that it’s HD. The person who originally created that has moved on in most contexts, so now we have to find someone else who’s going to be good in front of the camera that we can then reshoot and re-edit it in HD. And how long will that last until, I suspect, ultra-HD comes down the pike? Or, God help us, when the holograms start appearing? So that makes me nervous about will we ever catch up. We have hundreds of pages. What pages lend themselves well for interactive-talking sort of videos versus what pages are not going to change too quickly? That’s’ something that we’re struggling with. What do you prioritize? What do you emphasize? What do you put on the back burner?” – HARRY DENNY