Multiplier effect

G.I. Bill provided an educational opportunity that benefited multiple generations in alumnus Jay Zawacki's family

Jay Zawacki can look back and identify many ways in which his Purdue experience impacted the direction his life would take.

For one thing, it was in the Purdue Memorial Union’s music listening room that he met a persistent, Brahms-loving fellow student named Alice Acton.

After enrolling at the university in fall 1948, Zawacki got into a habit of grabbing dinner at the union and then visiting its music room to read and enjoy the records in its expansive listening library. One night, Acton entered the room and asked if she could play Brahms on the turntable, only to have her request rebuffed.

“No, I hate Brahms,” Zawacki recalled telling her.

She returned the next night, and Zawacki responded in similar fashion. A trend began to quickly emerge.

“I didn’t want anyone messing with my reading,” Zawacki said. “She came back the next day and the next day – I think she came back three or four days, and she always had the same question. Finally, I said, ‘OK, you’ve worn me down. I hate Brahms, but for you, we’ll play it.’ So, we put on some Brahms.

“After the record was over, I said, ‘OK, since I’ve been so mean to you, let’s go down and I’ll buy you an ice cream soda.’ She ended up being my wife.”

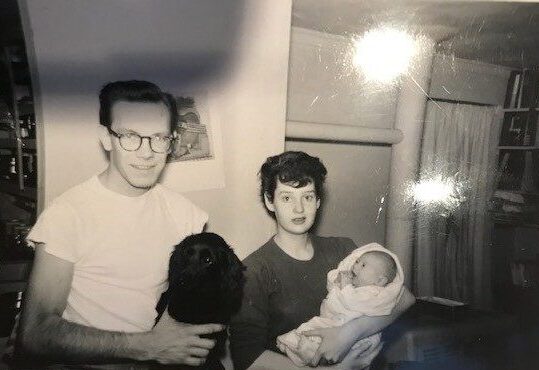

The couple initiated 68 years of marriage on Decoration Day, May 30, 1952, and went on to have four daughters, six grandchildren, and, to date, one great-grandchild – each of whom benefited from the educational opportunity the G.I. Bill afforded Zawacki.

“In general, [the G.I. Bill] brought into the mainstream of American life people who might not have been there. I certainly think that in my own case, that never would have happened,” said Zawacki, who grew up in a single-parent, working-class household in Paterson, New Jersey. “So what, in effect, the program did is it found there were a lot of smart people all throughout the class system.”

It was in West Lafayette that a self-described “comfortably mediocre” high school student and Army soldier discovered an interest in teaching that served Zawacki well as a professor at the University of Pittsburgh, West Virginia University, and in 35 years as a faculty member at Boston University.

By capitalizing upon that initial college opportunity, Zawacki also created a pathway for their children to attend a lengthy list of prestigious universities as undergraduate and graduate students.

“You could introduce that story again and again. None of that would have been possible without the investment that the government put into my generation of young men,” Zawacki said, citing the impact the G.I. Bill had on his family and those of many similarly accomplished Army buddies. “It’s important to understand that the multiplier effect does shape multiple generations.”

In a similar vein, Zawacki attended Purdue during a transformational period for liberal arts instruction at the university, decades before the emergence of the sprawling College of Liberal Arts we see today.

In that era, a significant divide existed among faculty members and administration about the purpose of a Purdue education. A prevailing campus attitude was that Purdue existed to train engineers and scientists, and if someone wanted to study literature or philosophy, they should attend a liberal arts college.

However, faculty members in the School of Science moved to introduce an experimental “Liberal Science” curriculum for female students in the 1939-40 academic year, aiming to provide this select group of women with a broad understanding of the important issues of the day.

Robert B. Eckles, acting director of the Liberal Science program, explained this objective in a July 1949 article for The Journal of General Education titled “Liberal Science at Purdue: An Experiment.”

“Courses in biology, chemistry, and physics were established with the end in view of teaching the information necessary to provide an intelligent citizen with an understanding of each subject and the role that it has played in making contemporary society what it is,” Eckles wrote. “To the group of courses in science were added courses in contemporary history and political institutions. With these courses were included those on world literature and the literature of twentieth-century science. Also courses in aesthetics, development of civilization, economic institutions, personal finance, and a study of the changing social position of women in an industrial age were included.”

Liberal Science functioned as a women’s honors program of sorts for nearly a decade until the first male students were admitted a year before Zawacki enrolled at Purdue. Veterans like Zawacki who enrolled after World War II had expressed great interest in learning about the humanities, Eckles explained.

“Many veterans had come to Purdue believing that studies in professional engineering were desirable or that some particular sequence of technical courses in the field of science was what they wanted,” Eckles wrote. “The desire to understand why they had been fighting, what modern civilization was, as well as the road on which civilization was moving were personal problems that many veterans found unanswered in their professional courses. As a result, many brought pressure on the School of Science to allow them to enroll in one or more of the liberal science courses. An unusually large number of men made application for admission to the Liberal Science curriculum.”

Zawacki was recruited to join the program entering his second year at Purdue, and he recalled taking a wide variety of courses including matter and motion; world ancient literature; political theory; U.S. and world affairs; early civilization; international relations; and English romantic literature.

Instead of taking an introduction to sociology course to which he was assigned, Zawacki requested that Professor Louis Schneider allow him to complete a directed-reading assignment. Schneider agreed and instructed Zawacki to read Karl Popper’s “The Open Society and its Enemies,” a dense work heavy on philosophy and science. Schneider met with Zawacki on a weekly basis to cover the week’s reading assignment and to explain any concepts his student struggled to understand.

By the end of the semester, Zawacki had started to follow Popper’s reasoning. Another of his professors actually offered an opportunity for him to deliver a lecture on the unusual reading material Zawacki often carried into class, unintentionally sparking a passion that previously had not existed within the young student.

“He knew I was taking the directed course because he saw me carrying this big, thick book. He asked me if I would like to give a class on this book, and I agreed,” Zawacki said. “I had so much fun with this class, explaining what Popper’s thesis was, and reading certain parts of the book and explaining it to the class. I so enjoyed it that I thought I would start my career and become a college professor. That’s what I did.”

He completed a bachelor's degree in general social sciences in 1951. A master’s degree in sociology would follow two years later. While at Purdue, the formerly indifferent student had gained a career and an appreciation for the many cultural endeavors to which he was exposed.

Describing Purdue as “a cultural oasis” in the region, Zawacki remembered as a college student attending shows featuring world-famous ballerinas and actors, foreign films, weekly lectures by prominent writers and philosophers, and even a performance by London’s Royal Philharmonic Orchestra with Sir Thomas Beecham conducting.

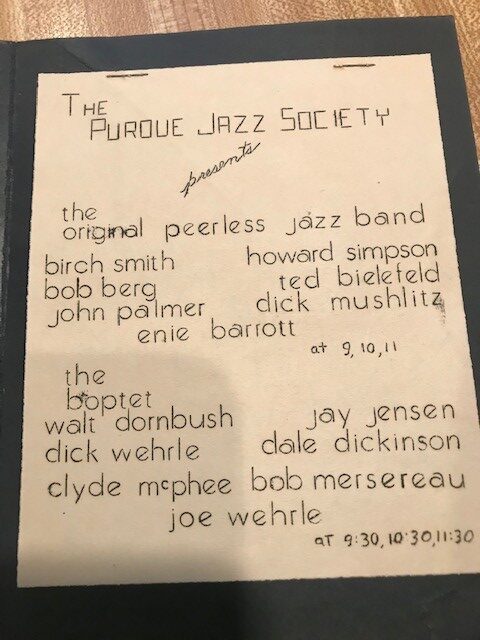

The jazz-obsessed Zawacki also helped found the Purdue Jazz Society with a group of friends and staged a concert for which he still has the flyer.

“Not only did we have these interesting and provocative classes, even after class you had all these other activities to go to that had a very high cultural standard,” he said.

Zawacki worked in higher education for four decades, most notably at Boston University, where his Liberal Science background produced an adventurous college professor. As a social science educator in BU’s College of General Studies, he developed a course for second-year students that examined the Chinese Revolution and the Russian Revolution and its aftermath.

The course involved far more than classroom instruction and reading analysis. For several years in the early 1980s, Zawacki annually accompanied dozens of students to Russia when the Iron Curtain was still very much in place.

Perhaps the trips were somewhat dangerous, but Zawacki felt they were the best way for his students to truly absorb the subject matter.

“After studying revolution, they wouldn’t be going as wide-eyed tourists looking at monuments,” he said. “They would have a grasp of the history of the Soviet Union and the Stalinist purges and things of that sort.”

This is just one example of the many ways that Zawacki said his Purdue experience transformed him. He credits that growth to the faculty members who recruited him into the Liberal Science program and identified an intellectual curiosity that would blossom under their instruction.

“Purdue gave me an identity, a character if you will, which its faculty nurtured and cultivated in me,” he said. “They gave me a gift which shaped my academic career and life.”

PURDUE AND THE G.I. BILL

Did you know about Purdue’s link to the creation of the G.I. Bill?While former Purdue vice president, treasurer, and controller R.B. Stewart did not actually write the American Legion-driven Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, some historians still recognize Stewart as a “Father of the G.I. Bill.”

Congress passed the landmark piece of legislation to provide World War II veterans with benefits like low-cost mortgages, business loans, and tuition and expense payments to attend high school, college, or vocational school. Stewart served from 1943-56 as chairman and administrator of the Veterans Affairs Advisory Committee on Vocational Rehabilitation, Education, and Training – the body that oversaw the program’s tremendous success.

By 1956, 2.2 million veterans had used the G.I. Bill to attend college – according to Stewart a small price for the government to pay in return for their service to the nation.

In her 1983 biography, “R.B. Stewart and Purdue,” Ruth W. Freehafer relayed comments Stewart made in a 1962 interview, saying that the G.I. Bill “recognized the disruptions and hazards of war especially affecting the wartime veterans. They earned this privilege and seriously used their opportunity. Being older, they needed to lose no time nor suffer further financial difficulties to move ahead at maximum capacity.”

The Lyndon B. Johnson administration in 1964 presented Stewart with a presidential citation that acknowledged his work as G.I. Bill administrator. The citation stated that Stewart “rendered conspicuous service through unstinting effort, wise counsel, courageous integrity, and forceful leadership in establishing sound principles for providing education and training for veterans and their orphans.”

Stewart was also one of the pivotal figures in Purdue’s ascension as a highly regarded research institution. During his nearly 40 years at the university, Purdue’s enrollment, financial security, and endowment experienced exponential growth. Stewart donated his home, Westwood, to the university in 1971, and Purdue’s presidents have resided there ever since.

In 1972, Purdue renamed the Memorial Center in Stewart’s honor. Since then, the multipurpose building – which houses the Humanities, Social Sciences and Education (HSSE) Library, Purdue Archives & Special Collections, the Loeb Playhouse, and Fowler Hall – has been known as Stewart Center.