24-Hour News and Special Interest Groups

In the 1980s, a large expansion of television networks occurred that would offer numerous new channels to viewers. CNN, the country’s first 24-hour news network, drastically altered the media landscape of the United States. Networks such as Fox News and MSNBC would soon follow, each offering very conservative and liberal perspectives on politics and current events. While 24-hour news networks should theoretically increase the overall political knowledge of votes and inform the public, they have had a largely negative impact on political discourse. Since their creation, 24-hour news networks have sponsored sensationalism and fueled partisanship between liberals and conservatives.

Increased Competition

The massive increase in the number of available channels created competition between networks for an increasingly small viewership and networks began targeting certain demographics of viewers. Most notably, networks created shows that would appeal to viewers with certain political preferences. The first two networks that typically come to mind are Fox News and MSNBC. Cass Sunstein, a University of Chicago law professor, believes that the creation of these politically-biased networks has polarized the American public between extreme liberalism and extreme conservatism and has promoted partisanship. He explains that, “with the multitude of choices available on television…media consumers will select only the outlets that they find the most comfortable or familiar. These viewers are deprived an opposing view and…are directed towards greater division.”

Techniques Used by Networks

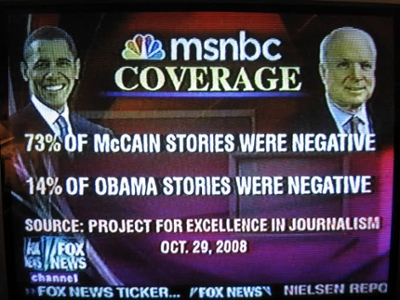

These networks use different techniques to reinforce their political messages. One technique is called “gatekeeping”, which is the process by which news stories are selected. By using this technique, networks filter out the stories that will not support their political ideals. Another technique is called “issue framing”. This is the process by which someone constructs and defines a story, placing emphasis on certain aspects over others. For example, issue framing was used during the 2008 presidential election. After Sarah Palin was chosen as John McCain’s vice presidential candidate, many conservative networks used issue framing to focus on Palin’s character rather than her level of experience to gain validation for her as a candidate. This is just one example of how issue framing has been used to further the political agendas of these news networks.

24-hour news networks have also turned to sensationalism to attract viewers. These networks emphasize certain stories that are more likely to grab a viewer’s attention. Matthew Baum, a political communications scholar, defines this as “soft news”. He claims that soft news has the following characteristics: “The absence of a public policy component, a sensationalized presentation, human-interest themes and an emphasis on dramatic subject matter, like crime and disaster.” Ken Gordon, a former Majority Leader in the Colorado State Legislature, claimed that, “the ignorance of the American people can be laid, in part, on the media.”

Soft news may also be used to legitimize their political perspectives. For example, many conservative networks broadcasted stories about the possibility of President Obama being a Muslim or being foreign-born in an attempt to discredit him. There was no evidence that either claim was true, but they grabbed the attention of conservative viewers and promoted partisanship. According to William Jacoby, a political scientist, issue framing is an “explicitly political phenomenon.”

How Candidates Adapt Their Strategies

Politicians, especially presidential candidates, have revised their campaign strategies to use the 24-hour news system to their advantage. The creation of 24-hour news networks caused the splintering of the American public into a variety of special interest groups whose news networks were tailored specifically to their belief. These special interest groups may include those who are pro-choice, Christian, or young adults. While there have always been segments of society that are divided along key issues or demographics, 24-hour news networks have intensified these divisions.

Politicians have used these politically-biased networks to appeal directly to these special interest groups on a more massive scale than ever before. By doing so, they target their party base and ignore the mass public when forming public policy. In the current presidential campaign, for example, each of the candidates is focusing their campaign on special interest groups that would give them the highest amount of votes. Donald Trump is focusing his campaign on the portion of the population that is anti-immigration. On the opposite side of the political spectrum, Bernie Sanders is focusing his campaign on economic problems and those who are dissatisfied with the current state of the economy. All of the candidates, whether Republican or Democrat, use news networks that share their political view as platforms for reaching these groups.

The introduction of 24-hour news networks into the American media system should have been an important step toward informing the mass public on political issues and candidates, increasing the effectiveness of the electorate and leading to an improved political situation throughout the country. However, using sensationalism, issue framing, and gatekeeping, these networks deepen the partisan divide in the public and portray partisanship as being predictable and understandable. These 24-hour news networks are responsible for what may be the most politically divided American public in the country’s history.

Sources:

Cohen, Jeffrey E. The Presidency in the Era of 24-Hour News. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2008.

Dagnes, Alison. Politics on Demand the Effects of 24-hour News on American Politics. Santa Barbara, California: Praeger, 2010.

“Media Coverage in the 2012 Election.” C-Span video, 53:30. March 2, 2012. http://www.c-span.org/video/?304713-1/media-coverage-2012-election.

Paletz, David L. The Media in American Politics: Contents and Consequences. 2nd ed. New York: Longman, 2002. 209.