Vehicle for change

The American criminal justice system has evolved considerably over the last century. The driving factor behind that evolution? The emergence and adoption of the automobile

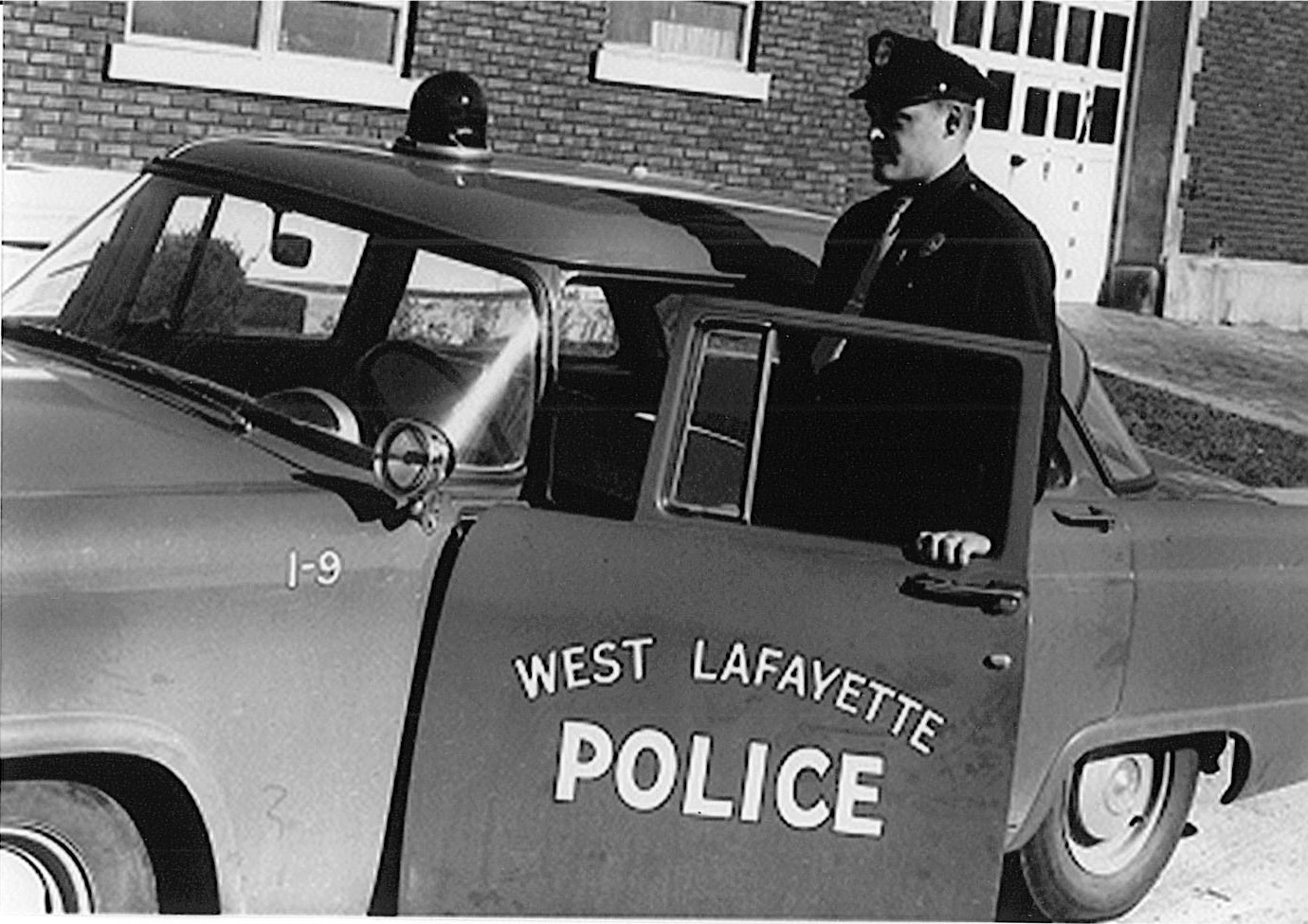

The nature and scope of American policework underwent massive change across the last century, and one factor drove much of that evolution: the automobile’s emergence as a viable, and eventually dominant, form of transportation.

The car’s role was so pivotal, in fact, that Spencer Headworth, an assistant professor of sociology, developed an entire course around its impact on the criminal justice system.

“Early on in the 20th century, the car emerges and grows really fast and that pretty much immediately changes the way the criminal justice system works, the kind of situations that law enforcement officers have to deal with, and the legal issues and Constitutional issues that arise,” said Headworth, who likes to say his criminal justice course (SOC 328) provides a “car-window view” of this metamorphosis.

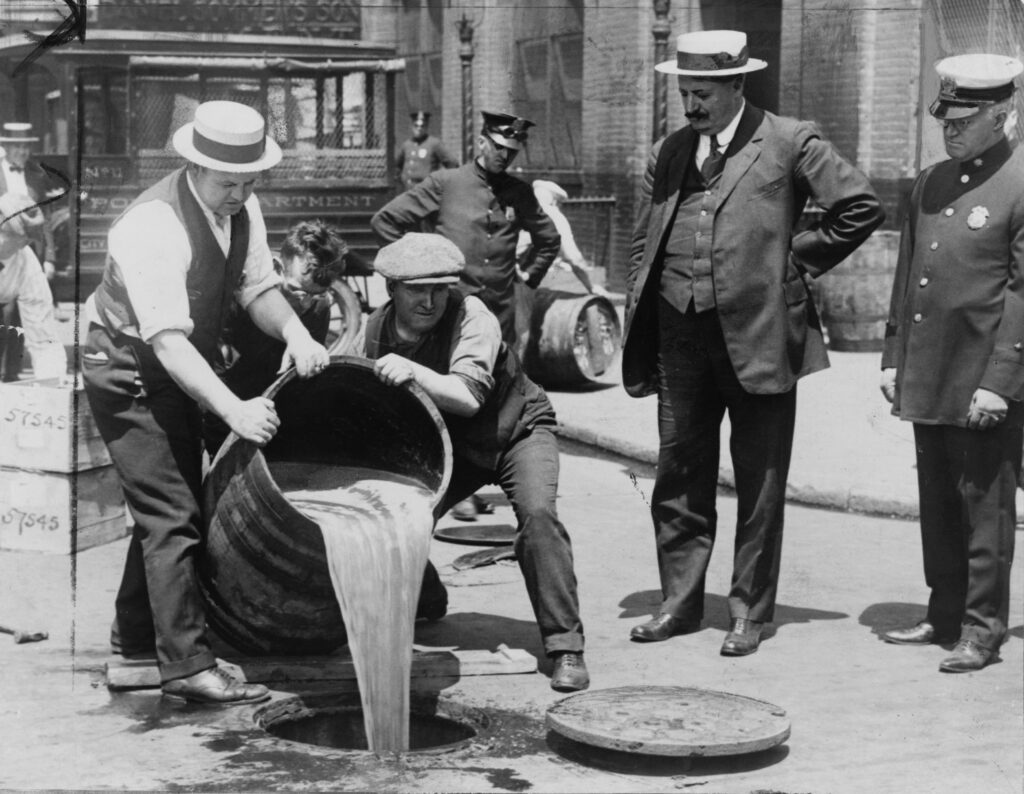

Beginning with police efforts to enforce Prohibition laws and battle organized crime in the 1920s, the car was often part of the equation as law enforcement, civilians, and the court system grappled with an increasingly complicated set of societal questions.

- To what extent is a private car driven on a public road protected by the Fourth Amendment’s language barring unreasonable search and seizure of personal property?

- How should communities treat vehicle-related crimes like driving under the influence or auto theft?

- What are the most effective and necessary methods of battling interstate drug and human trafficking?

- How should the criminal justice system address the racial disparities tied to vehicle stops indicating that Black drivers are twice as likely to be pulled over as White drivers?

- As technology evolves, what are the legal and ethical guidelines that officers should obey when using surveillance tools to investigate suspected criminal behavior? What prevents them from unnecessarily spying on law-abiding citizens?

“I never really thought about the fact that there was a point in time where the position that police held was not thought of as being as powerful as it is today. I think now it’s even more relevant with police brutality becoming something people are talking about,” said Julia Ware, a junior in law and society from Dallas. “It’s interesting to see the beginning of that institution and the way it’s changed over time and how it has become what it is today. The power that they are able to wield today, they didn’t always have.”

The car’s introduction inspired that change, as it provided criminals with a newfound ability to rapidly escape from the scenes of their crimes.

“Prior to this, you have people getting away on horses and things, but there was not this widely available, really rapid means of leaving the scene of a crime and also crossing jurisdictional boundaries – leaving a town into the county, leaving a county into a different county, moving in between states,” Headworth said. “All this stuff creates lots of issues for the criminal justice system, so the rise of what we now recognize as modern police departments in substantial part was about motorizing police departments to be able to respond to this new environment of criminal offending and potentially people getting away.”

At roughly the same time, the Prohibition era increased law enforcement’s motivation to search personal property – a ubiquitous police practice today that had not been especially common prior to the push to stamp out illegal alcohol.

“Talking about Prohibition along with the car has been interesting, just in how we see the repetition nowadays with drugs versus alcohol back in the 1920s,” said Nisha Sen-Gupta, a junior from Long Grove, Illinois, double majoring in law and society and brain and behavioral sciences through Degree+. “It’s interesting to talk about the parallels that we’re seeing a century later.”

Vehicle stops have been an ongoing source of controversy, prompting courts to weigh in on the warrant requirements involved with searching a privately owned vehicle while it is being operated in a public space. Headworth pointed to a 1925 landmark Supreme Court decision, Carroll v. U.S., that upheld the constitutionality of warrantless search.

“That decision creates the vehicle stop as this kind of unique form of citizen-state interaction that we didn’t really have before and sets the groundwork for a lot of Fourth Amendment jurisprudence going forward,” Headworth said. “A lot of the subsequent developments in the Fourth Amendment and citizen rights relative to government power and law enforcement authority arrive more or less directly out of this circumstance created by the proliferation of cars.”

As the course progresses, Headworth details additional developments that impact police interactions with the public today, including the construction of the interstate system, car-based policing that increases the distance between officers and the communities they patrol, and the rise of police-related infotainment shows like “Cops” and “America’s Most Wanted” that use car chases as sources of dramatic tension.

He also examines 21st century technological developments like red-light cameras, speed cameras, GPS tracking, and automated license-plate readers. By focusing on how law enforcement’s use of these tools intersects with trends spanning America’s criminal justice history, Headworth encourages students to consider its future.

“We talked a lot about interstates and, when cars became more up-and-coming, how that created new crimes like trafficking and what that meant for federal and state governments,” Sen-Gupta said. “I think in the future, you can see similar things starting to happen where we’re creating new problems. Now with the introduction of self-driving cars, maybe we’ll see the need to create new solutions for things that weren’t problems in the past, but now are.”

Spring 2021 was Headworth’s first semester teaching the course, but he is already in the process of turning the car-based curriculum into a textbook, tentatively titled “Rules of the Road: A Car-Window View of American Criminal Justice.” In March, the College of Liberal Arts also recognized Headworth’s innovative approach by naming him one of its three Excellence in Discovery and Creative Endeavors Award winners, joining Laura Zanotti (anthropology) and Jennifer Hoewe (communication).

He said the course’s primary objective is to outline the criminal justice system’s evolution using a relatable approach that motivates students to consider how these issues affect all citizens.

“It’s fundamentally something that I thought nearly every person who’s spent significant time in the United States could personally relate to, which is at least riding in a car, if not in most cases driving a car,” Headworth said. “That ties to one of the core things that I hope students will take away, is feeling a sense of connection to these issues and some buy-in on this idea that criminal justice isn’t just something that affects people who we think of as quote-unquote criminals. It’s a core element of our life, it’s a form of governmental power that affects all of us, and it’s something that we all have connections to.”